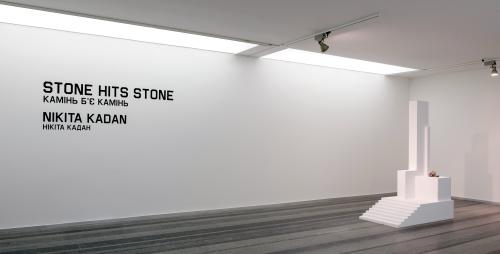

Nikita Kadan: Stone hits stone. The past as an urgent now

8 september, 2021

“To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it really was’ (Ranke). It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger“¹

The historical past, in the form of ideologies, art and acts of political violence, lies at the heart of Kadan’s oeuvre. He delves into works of the Ukrainian Avant-Garde and engages with the history of the last century in Ukraine. From this perspective, it seems fitting that his first large-scale solo-exhibition in Ukraine, Stone hits Stone, opens with a memory expressed as an intuitive art-historical reflection, mainly through works from those counted among the Ukrainian Avant-Garde. The works celebrate the Soviet revolution (Victor Palmov) and are testament of a Soviet ideology that merged with communist theory and practice (Vasyl Yermilov). Others emphasize Ukraine and its cultural identity (Ivan Padalka) and the subject of political violence against those who identified as Ukrainian (Sofia Nalepynska-Boychuk) and by among others Ukrainians against minorities (Manuil Shechtman and Marc Chagall). Kadan juxtaposes his own work, Tiger’s leap (2018) to this historical reflection. The sculpture displays iron replicas of improvised weapons fashioned from tools used in industrial metallurgy during the early 20th century, in what was then the Russian Empire. Such weapons were used by factory workers in a failed uprising in 1905 in Horlivka, an industrial city in the Donetsk region. The revolt was violently subdued by the military, but this act of resistance was one of many that laid the groundwork for not only the successful revolution of 1917 and the start of the Soviet empire, but also the enthusiastic belief in a Soviet utopia that would be vividly expressed by the artists of the Avant-Garde.

Tiger’s Leap, is one of Walter Benjamin’s most well-known concepts. Applied to the work of Kadan, Xin Feng & Kiera Chapman’s reading of a tiger’s leap comes to mind: “a ‘tiger’s leap’ into the past rejects the idea of time as linear and sequential in favor of a creative use of past example that breaks with the temporal continuum. The ‘tiger’s leap’ allows people to seize on the past as a source of difference and thus to draw attention to new possibilities for change in the present.”. Kadan, throughout the exhibition, makes a series of ‘tiger’s leaps’ by appropriating historical events, objects and designs, and reinterpreting them with a contemporary urgency — an urgency to resist geopolitical failures, extreme right ideologies and neo-liberal forces.

An example is Victory (White Shelf) (2017), a work reinterpreting Vasyl Yermilov’s (1894-1964) unrealized sculptural composition entitled Three Russian revolutions: 1825, 1905 and 1917. Yermilov, one of the leaders of the Ukrainian Avant-Garde and a predominant inspiration for Kadan, worked in constructivist tradition seeking to express ideology mainly through geometrical constructs, seen as the creative organizing principle of art. For his Three Russian revolutions: 1825, 1905 and 1917, he constructed a logical argument on history, embracing the consciousness of a then new society. Examining Kadan’s piece, Yevgenia Belorusets explains Yermilov’s work by saying: “...(the) several surfaces of the sculptural group united become an embodiment of history, its code. Each surface in his exceptionally concise construction comes across as a sign of a particular historical event”. Kadan revives this sculptural composition but radically transforms the carefully constructed surfaces of Yermilov. Instead, he chooses to recreate the work as a pure white form. “Three revolutions become a ‘Victory’; to align historical events in a certain significant order seems pointless. Kadan moves the absurd nature of the ‘rational’ formation of revolutions in a composition of concise forms into a chaos of meanings, in which any of the events appears in the shape of a single Victory”. Belorusets points out that Kadan refuses the rational approach to history embedded in the original work of Yermilov, recognizing it as a single form which evokes a chaos of meaning. The interpretation of Kadan becomes even more consequential when his choice of material is taken into account. The work is translated using white painted plasterboard, a mass-produced building material. For Kadan it is a symbol of what is known as “євроремонт” and is inherently generic. What is more, because the inner properties of the material do not have a relation to its outer content, its use becomes problematic in constructivist ideological terms. Nevertheless, it serves the rigid conceptualization of the work, reducing the “original ideology” and making Victory a shell, offering, on one hand, space for a (re)new(ed) utopia, and on the other hand, formulating an urgent critique of Ukraine’s relationship to its own (unwanted) history. This critique is further complicated by the transformation of the sculpture into a White Shelf (or a Pedestal) which carries an object retrieved from a destroyed house in Lysychansk (a city previously in the warzone in eastern Ukraine). By including this object of ongoing war (history in the making), Kadan completes his ‘tiger’s leap’ and reorients history entirely towards the present and future. This allows Victory (White Shelf) to remember the past while being a piece of evidence of an ongoing war (the present) and an undecided monument for an uncertain future.

The transformation of Yermilov’s sculptural model into a pedestal fits a long-term interest of Kadan into the ideological meaning of the avant-garde pedestal. Over a period that lasted longer than a century, heroes and ideologies shifted continuously. Throughout this time, public monuments changed accordingly. But with all those changes, very often the pedestal itself, which in constructivist tradition was an expression of ideology, stayed untouched, carrying a new temporal hero. The first monumental work devoted to this subject is Pedestal. Practice of Exclusion (2009-2010), a near 6-meter large Avant-Garde inspired pedestal made of the same white-painted plasterboard material, installed into a 6-meter-high space. As a result, the pedestal became the sculpture itself, refusing its role of servitude while emphasizing its original ideological narrative. With this work, Kadan urged a reconsideration of the political framework in which national memory is defined and cultural heritage becomes censored and destroyed. It criticized the ongoing war on monuments in post-Soviet Ukraine, a war that till this day is costing Ukraine essential parts of its heritage. Although Kadan continued his interest in the pedestal itself, the notion of the ‘monument’ is a more poignant departure point to understand his works. Victory (White shelf) and Pedestal. Practice of Exclusion are first and foremost modernist and avant-garde designs which Kadan transforms into monuments because they are a testament of the Soviet utopia. This appropriation and transformation of historical forms doesn’t suggest history might or should be repeated, but rather that history is a way to enlighten the present.

This understanding is most urgently embodied in Victory, as well as in the newly produced Lysa Hora Architecton (2021). This monumental new work, installed in the same space where Pedestal. Practice of Exclusion was first shown in 2011 (coming full circle), draws on a series of “architectons”, drawings and later plaster block models by Kazimir Malevich exploring the notion of cosmos and “cosmic cities”. They embodied Malevich’s efforts to translate the suprematist principles of composition to three-dimensional forms and architecture. This work, made in a time and place where artists and especially architects internationally (far beyond the Soviet Union) were drawn to the belief that the socialist revolution offered the prospect of imminently realizing their most utopian dreams. This belief in an imminent utopia, inherently embedded in the architectons, is juxtaposed to “a burned house” installed instead of the original black circle of Malevich’s Architecton. In doing so, Kadan replaces the notion of cosmos and utopia with that of a violent reality. The burned house makes reference to the attack in 2018 on a Roma encampment in Kyiv by a paramilitary organization C14 (Ukrainian extreme right nationalists). They rounded up the families and led them away from their homes, which were subsequently burned. This modern-day pogrom shamed Ukraine, a reference that is made explicit by the adjoining lightbox showing an image and new paperclipping of this horrifying event. The sculpture in this sense offers a steep warning against the dangers of politically driven violence that through fascist ideology threatens to hijack nationalism. The burned house is equally a stain on the utopian dreams voiced by socialism, while the sculpture expresses an ideological clash that echoes the binary world views dividing today’s society at large, both in Ukraine and on the global stage.

Kadan’s monuments to failures of society and political violence emphasize (national) memory as a tool of societal definition. It makes ‘politics of memory’ an essential battleground within the political arena, by definition the subject of manipulation, and never about “the way history really was”. This makes Kadan’s practice a form of resistance, voicing memory as a part of a public debate not ‘managed’ by the political class. An example of this is seen in the work Pogrom (2016-2017). A series of large-scale drawings that are based on photographic evidence of the pogrom that took place in Lviv early July 1941, in the days following the occupation by the German forces. Over a period of 4 weeks, over 4000 Jews were murdered. Although initiated and encouraged by the occupiers, the pogrom was carried out by (among others) Ukrainians who were part of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). The participation of Ukrainian nationalists was long disputed but has become apparent through research and testimonies, particularly in the work of professor John-Paul Himka, who not only names the OUN but includes the urban crowd, composed of both Poles and Ukrainians, with those who took part in robberies, sexual assault, beatings and murders. The photographic evidence was captured by the German occupiers, and each drawing stays true to the composition of its source photograph. Kadan only permitted himself to make slight crops, maintaining the gaze of the photographers, who were in this case German officer or military journalist. The viewer is thus following the gaze of the perpetrator. This position forces the viewer into the uncomfortable position of looking at the crime as if witnessing the event itself. This unapologetic repetition of the perpetrator’s gaze, combined with Kadan’s aggressive and dynamic drawing technique and the large scale of each work, makes the images difficult to forget (resisting removal from history). At the same time, through the act of interpreting and naming documentary evidence of cruelty, he again exposes risks embedded in nationalism and its connection to fascist ideology.

The subject of political violence, embedded in binary world views, moves us through the exhibition, both in direct and indirect ways. A key work for this is The Inhabitants of Colosseum (2018). The work appears first as a sound piece at the start of the exhibition but is not named or explained until the very end of the exhibition where it returns in a different form. As a sound piece, one hears the sound of 400 pairs of wooden clogs walking together over a stone bridge (the work at the start of the exhibition has no caption nor any textual reference). The sound itself is a remnant of a 2018 performance in Regensburg, which took the form of a call to public action by Nikita Kadan in remembrance of over 400 prisoners, who were stationed at the Colosseum boarding house, a satellite of the Flossenburg concentration camp between March 19 and April 24th, 1945. During their internment, the prisoners were forced to repair damaged railway connections, marching daily from the camp over the stone bridge in Regensburg to the railway worksite, wearing wooden clogs. Over a period of 5 weeks, a tenth of the prisoners died. The choice to leave this sound work unnamed and unexplained at the start of the exhibition allows for the installation to move beyond its original intent, becoming duplicitous. The deliberate manipulation invites an initial reading of the work within the context of the first spaces and works the viewer encounters, with suggestions of Marxist ideals, revolutions and farmers’ resistance. The fascist narrative, inherent to the work’s original meaning, is only revealed at the very end of the exhibition, complicating the encounters that followed the first display of The Inhabitants of Colosseum. This confusion obliges the viewer to revisit the preceding works and rethink the implications of fascist history and ideology, in relation to both Ukrainian historical narratives and contemporary challenges within Ukraine and in a global context.

The Inhabitants of Colosseum is both the false beginning and the end of the exhibition. In the last room, it takes the form of documentation and stands in conversation with Anonymous, Tarred (2021), yet another monument, and a new large scale charcoal drawing inspired by Yermilov remembering the Internationale. The sculptural form of Anonymous, Tarred is informed by sculptural exercises, or “volumes”, developed by students of the avant-garde at the VKHUTEMAS workshops in Moscow in 1920, under the guidance of Anton Lavinsky. These volumes represent the legacy of Soviet ideology, a legacy Kadan dramatically comments on by covering the monumental form with black tar, while placing it on a traditional white marble plinth. This blackened volume is the counterpoint to the white Victory. White was as much a shell as it was a utopian expression of ideals, while the gesture of covering the sculpture with black tar, on the other hand, is an act of desecration symbolic to how the politics of memory engages with history and heritage in Ukraine, which simultaneously declares the death of the Soviet utopia. However, through the act of placing it respectfully on a white marble plinth, the importance of that utopia is preserved as a memory in the face of an implied dystopian future. Anonymous, Tarred, a blackened Soviet legacy, and The Inhabitants of Colosseum, a fascist history, represent two ideologies that defined the 20th century. While the struggle between those two ideologies might have been paused (or came to an end), it emphasizes the binary logic and violence, rather than ideology, that survived and continues to divide the globe in the 21st century.

With an acute sense of urgency, Kadan continues to revive throughout this exhibition moments, images or artworks from the past century as ‘an urgent now’. And yet, all the works move beyond historical facts, making the question of memory itself the issue, while exposing and opposing the political injuries done to it. Stone hits Stone is never about “history as it really was”. It is a motive that flashes up in a moment of danger. It enlightens our present and orients us towards the future.

This text was first published in the book released on the occasion of a solo exhibition by Nikita Kadan Stone Hits Stone and within the framework of the PinchukArtCentre Research Platform. The book consists of texts by William Blaker, Bjorn Geldhof, Kateryna Mishchenko and Kateryna Iakovlenko, which tell about the artistic practice of Nikita Kadan and the works presented at the exhibition, as well as reveal the themes of history and memory, artistic interpretation of the past and violence and actualization of the avant-garde heritage of today.

Support us on Patreon to read more articles about Ukrainian contemporary art.Share: